Reflecting on the 1994 Denver Gold Show, Gold, and Gold Mining 30 Years On

Text of a presentation delivered at Gold Forum Americas by Daniel McConvey, Rossport Investments LLC

What follows is an abbreviated write up of a recorded talk at Gold Forum Americas. clicking on the link https://www.goldforumamericas.com/keynote/165/

We got sentimental last month realizing that it was 30 years since we attended our first Denver Gold Show (now Forum) in 1994 at the Westin in downtown Denver. We wanted to say something about what the industry was like then and what our key observations and reflections are in the ensuing years since. We also wanted to offer some suggestions for investors new to this sector.

Before I continue, I would like to say that the Denver Gold Show, which started in 1989, was a class act when I first went in 1994. It was then under the strict and detail focused leadership of Michele Ashby. Tim Wood and his Denver Gold Group team continue maintaining that high standard and work continuously on making the Forum better.

The World and the Gold Industry in 1994

1994 saw the ending of Apartheid with the election of Nelson Mandela as President in South Africa. There was hope in the Middle East between Israel and Palestine with Noble Peace Prizes being awarded to Shimon Peres, Yitzhak Rabin and Yasser Arafat. The opposite of where we are today. On the negative side, heavy weapons pounded Sarajevo and there was genocide in Rwanda.

Gold was around $390 per ounce. The US Congress was about to fail in its effort to pass mining law reform which would have likely brought a 3% gross royalty on federal lands and better ability for the public to launch citizen lawsuits against companies and agencies. During my first month on Wall Street, I spent a day with a group in Washington lobbying members of Congress on behalf of the industry. In May of that year, Secretary of the Interior, Bruce Babbit was forced by a federal judge to sign over the patent for 1800 acres of Goldstrike property in Nevada to Barrick. He had defiantly held out for about a year.

Barrick, which I had just left, was under the leadership of CEO Peter Munk and no-nonsense President Bob Smith. It was ramping up production towards two million ounces a year at its Betze- Post open pit mine at its bonanza Goldstrike property in Nevada. The autoclave processing build and execution team was under the leadership of Ken Thomas. Reflecting back on it, the mine and process ramp up went very smoothly. Barrick’s share price had outperformed as a result. We were proud of that ramp up then, but it seems even more impressive looking back. The last of the six autoclaves were commissioned earlier in the year and the feed grade through those facilities was near 0.3 ounces per tonne. Ground was being broken on the nearby underground Meikle Project. Barrick had bought the Goldstrike property in 1987 and soon made one of the biggest gold finds in history. In hindsight, I wish we had not mined Goldstrike so fast. Those bonanza grades saw little of the high gold prices of the next decade.

Barrick was also completing the acquisition of Lac Minerals, a gold major, whose prize assets were the Chilean Andes located El Indio mine and the Pascua-Lama project. That acquisition did not work out for Barrick and the pursuit of the Pascua-Lama project has been disastrous for Barrick to date in our view. It has yet to be completed and has cost Barrick billions of dollars and reputational damage in Chile. In the ensuing decade or so, Barrick would buy the other two large North American producers that existed in 1994, Homestake Mining (one of the oldest companies on the NYSE) and Placer Dome. The latter purchase has been a very good one, especially with the continued success at Pipeline.

Newmont’s new CEO in 1994 was Ron Cambre who joined from Freeport. His CFO was Wayne Murdy who would succeed him as CEO. Newmont was just finishing its own Nevada expansion that was launched seven years before in reaction to a corporate raid by T. Boone Pickens. That 1987-1988 raid also led to a poison pill dividend of $33 a share financed by the sale of its numerous non-gold assets and a lot of debt issuance that weakened the balance sheet for several years. Newmont had just started production at its majority owned Yanacocha mine in Peru the year before. Peru at the time was fighting the terrible Shining Path insurgency. At the time of that 1994 Gold Show, we had just completed a group site visit to Yanacocha. Yanacocha went on to exceed all expectations over the next decade replacing Goldstrike as the world’s largest gold mine. Also on Newmont’s drawing board was the development of the estimated $1 billion Batu Hijau copper gold project in Indonesia (now run by PT Amman Mineral Nusa Tenggara) that was to become one of the most expensive mining projects ever built to that time.

In the ensuing seven years Newmont would go on to consolidate, Santa Fe Pacific Gold which owned the Twin Creeks mine in Nevada, Battle Mountain Gold, Franco Nevada (in its first incarnation), and Australia’s Normandy Mining.

The decade before the 1994 Denver Gold Show was a heyday for the industry, gold investors and gold analysts. Gold rose from its depressed levels of 1985 and many mining companies chased the market premium given to pure gold companies by becoming pure gold companies. These included Newmont, Barrick, Placer Dome, Sante Fe, Battle Mountain, Amax Gold and others. Institutional Investor Magazine created a separate category for Gold Mining which lasted until around 1995. Valuations for gold stocks were high. 1987, the year I started at Barrick, was a key year in the industry with the T. Boone Pickens Newmont raid, the formation of Placer Dome, and Barrick’s huge Goldstrike discovery. There were numerous equity raises to finance mine expansions. The October 1987 stock market crash that year cooled things off and ended equity issues for some time. The fall off of gold prices in 1991-1992 hurt as well.

Despite that crash and fall off in gold prices, the late 1980’s boom in gold prices, gold mining equity prices, company financings, and gold discoveries in Nevada, Australia and elsewhere led to a boom in global gold production. By the end of 1994, global gold production had grown over 60% (900 tonnes) to 2,300 tonnes in a decade. In the 30 years since, global gold production has not increased as much in percentage terms.

As per Exhibit 1 below, the period 1987 to 1994 experienced a dip in gold prices mainly due to three reasons. First, as noted, global gold production increased. Second, the Maastricht Treaty, which effectively set the structure of the Euro and the European Central Bank, was being negotiated. It was signed in 1991. We think this movement towards European monetary policy consolidation motivated Europe’s first significant post war central bank gold sales by Belgium and The Netherlands in that period. Third, there was also the impact of producer gold hedging that became attractive in Australia, which had very high interest rates in the late 1980’s, and with some North American producers including Barrick. However, in 1994 with the gold price at around $390 and heavy further central bank gold sales not forecast, these factors looked digestible. Unfortunately, a storm was brewing.

High interest rates in 1988-1989 especially in Australia motivated producer hedging. Newcrest realized contangos of in excess of 15%. Belgium made the first major European Central Bank gold sale in 1989.

Exhibit 2 is a copy of our 1994 initiation report at Lehman Brothers. The theme was “It’s A Whole New World”. The cold war was over and the North American industry’s landscape map for opportunity had multiplied. Valuations were high. The Premium Valuation Ratio we used (effectively zero discounted NPV) was over 1.6 and the 1995 estimated P/E was 33. Of the seven companies we picked up coverage on, only Newmont still exists. We picked up coverage on Barrick later. We were wrong in thinking that the industry would not repeat its mistakes of the late 1980’s in overspending on projects. We were also wrong in believing that central banks were unlikely to allow negative real interest rates again.

In October 1994, we published our Initiation of Coverage with the theme “Gold Mining: It’s a Whole New World.”

With the Cold War over, the areas of the world to explore and invest in grew hugely.

Lehman Brothers Premium Ratio Valuation (estimating profit on recoverable reserves) was 1.63.

There were over $1 billion of write offs in the previous four years. Average forecast 1995 P/E at $390 gold = 33.

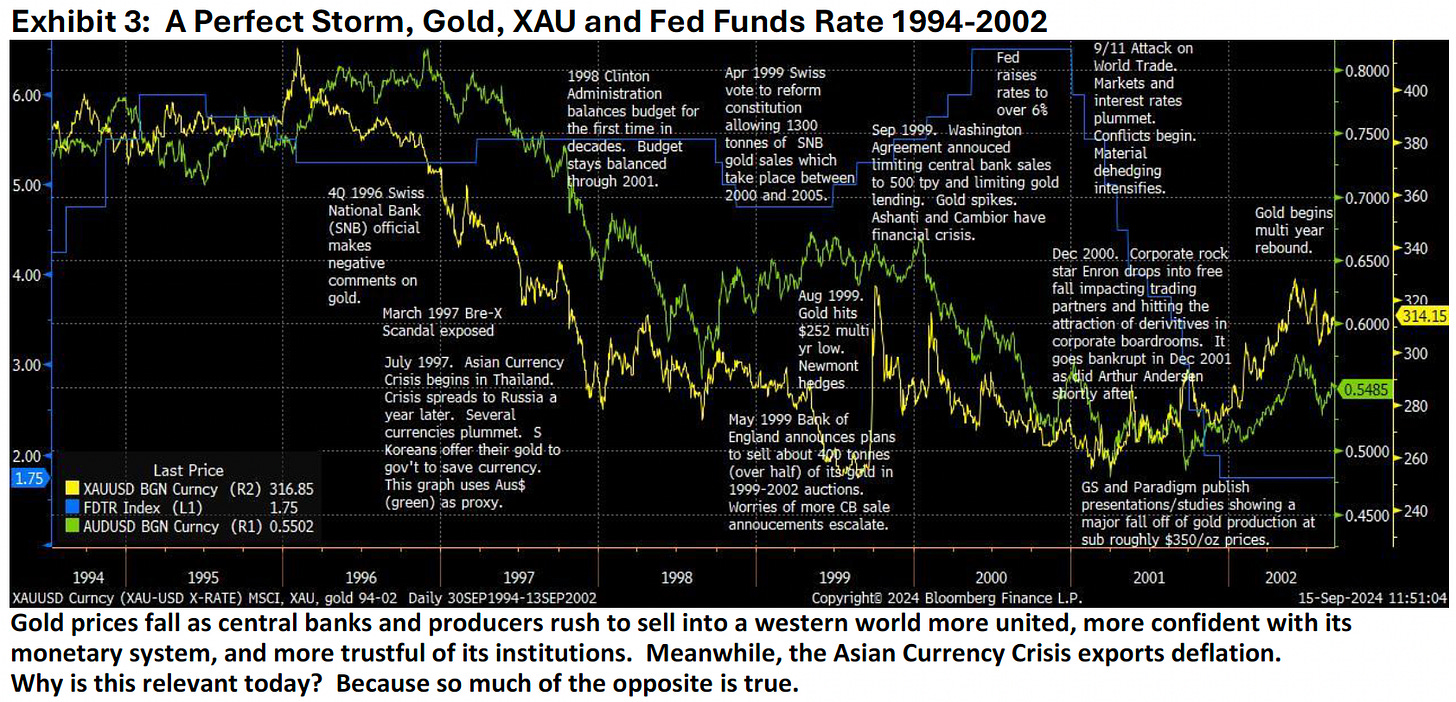

The Perfect Storm for Gold 1994 to 2002

Things stayed steady in the gold market for about two years after that 1994 Denver Gold Show. Then, as outlined in Exhibit 3, mayhem took place. Confidence in western currencies reached a peak with inflation tamed and the formation of the Euro. Several more European central banks led by the Swiss seemingly rushed to beat each other to sell gold. The Asian currency crisis caused a collapse in several Asian country GDP’s and currencies. The Australian dollar fell below $0.50 (which helped protect Australian miners). South Koreans answered the call of their government to turn in their gold jewelry for Korean won. Heavy producer selling added downward pressure to the gold price. The price bottomed out at $252 an ounce in 1999.

Gold prices fall as central banks and producers rush to sell into a western world more united, more confident with its monetary system, and more trustful of its institutions. Meanwhile, the Asian Currency Crisis exports deflation.

Why is this relevant today? Because so much of the opposite is true.

We think this 1994 to 2002 (and especially 1996-2002) period is important because the factors that were present then are near the opposite now. Trust in currency and institutions in general is falling. Central banks are now buyers of gold. Producer hedging is rare. The deflationary impact of Asian output has run its course, and we are now faced with inflation pressures by aging populations.

The Washington Agreement in September 1999 was a huge turning point that began calming that Perfect Storm. In that agreement, European central banks agreed to limit sales to 400 tonnes per year for five years and limit lending. Gold temporarily spiked from $255 to $325 per ounce causing major credit problems with hedged gold producers Ashanti and Cambior. I remember Cambior CEO Louis Gignac courageously coming to the 1999 Denver Gold Forum to “face the music” and report on the situation during that crisis. He was given a standing ovation.

The storm though was not over. The gold price would fall again to near that 1999 $252 low in 2001 under the pressure of heavy central bank sales, weak Russian and Asian economies and high US interest rates. However, the Washington Agreement had more than set the floor by eliminating panic. Hedge books began reversing. 9/11 was the next significant milestone. In 2002 the gold price was on the mend albeit slowly.

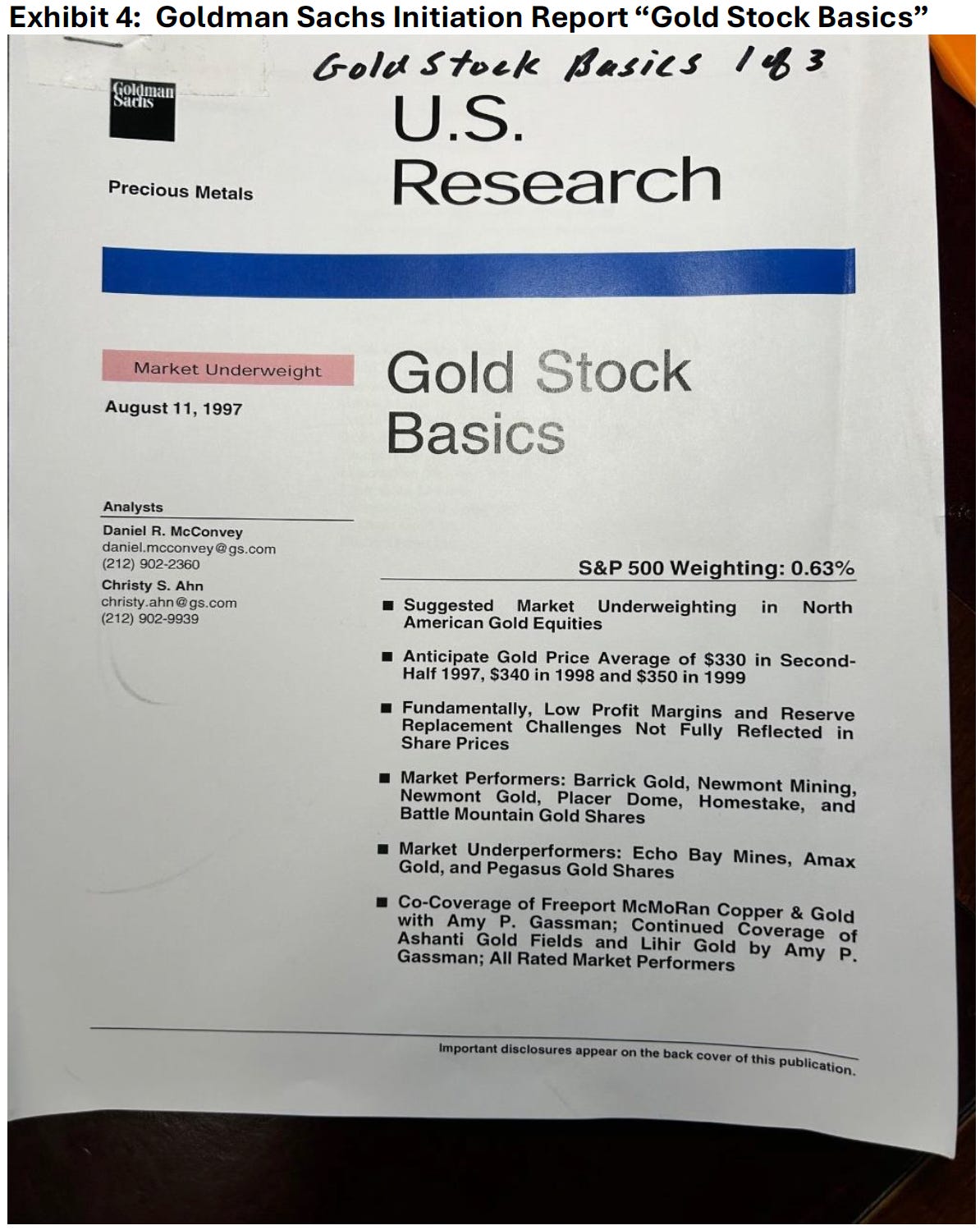

Gold Stock Basics 1997

As per Exhibit 4 we launched coverage at Goldman of “Gold Stock Basics” a month after the Asian Currency Crisis started in Thailand. Gold was at $330 per ounce and the XAU (Philadelphia Stock Gold and Silver) Index was at a relatively high 102. Our research director Steve Einhorn provided some sober guidance of how the gold mining industry looked to a generalist investor. It was not economic. We introduced 5% DCF analysis. Even at $400 gold prices the NPV multiple based on proven and probable reserves was 2.7. It seemed crazy even then. We launched with an underweight rating. With a one-year outlook we got that initiation rather right as things deteriorated from bad to worse.

Our August 1997, Goldman initiation report “Gold Stock Basics” came out a month after the Asian Currency Crisis started. We were bearish. Gold was at $330 and the XAU at 102 (vs. today 160). Even at $350 gold miners were at break even. Things got worse.

We introduced NPV analysis. Our price to NPV multiple at $350 and $400 gold was 3.7 and 2.7, respectively.

“We believe the industry is operating at break-even. We estimate the total future cash outlays of recovering gold, including general and administrative (G&A) costs and future capital expenditures, at an average of $300 per ounce. Based on this figure and current spot gold prices, current unit cash margins will be less than $25, or 10% of revenue. However, this does not include exploration and financing costs, which currently run $30-plus per ounce. Given exploration and debt-servicing needs, we believe that the gold industry requires a 33% operating margin (which would currently require a gold price of about $400 per ounce) in order to be attractive. Currently, only Barrick achieves this margin, mainly due to its hedge position.”

“ROE in the gold industry appears to be in a period of secular decline”.

In 1999, we became the first major US bank to launch coverage of a South African producer when we launched on AngloGold. I have stayed close to the company ever since. Coverage of Gold Fields followed.

market set off by the Washington Agreement, 9/11, the successful creation of gold ETFs and the 2008-2009 financial crisis. The huge leg up the last five years has been fueled by the Covid low- interest rate asset bubble, US political upheaval including the 2021 riots at Capitol Hill, the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and the war started by the Hamas attack in Israel in 2023.

After 9/11 Hedge book elimination is accelerated, Central banks start buying, and new gold ETF’s take off.

The Global Financial Crisis, Covid and other crises help erode trust in institutions.

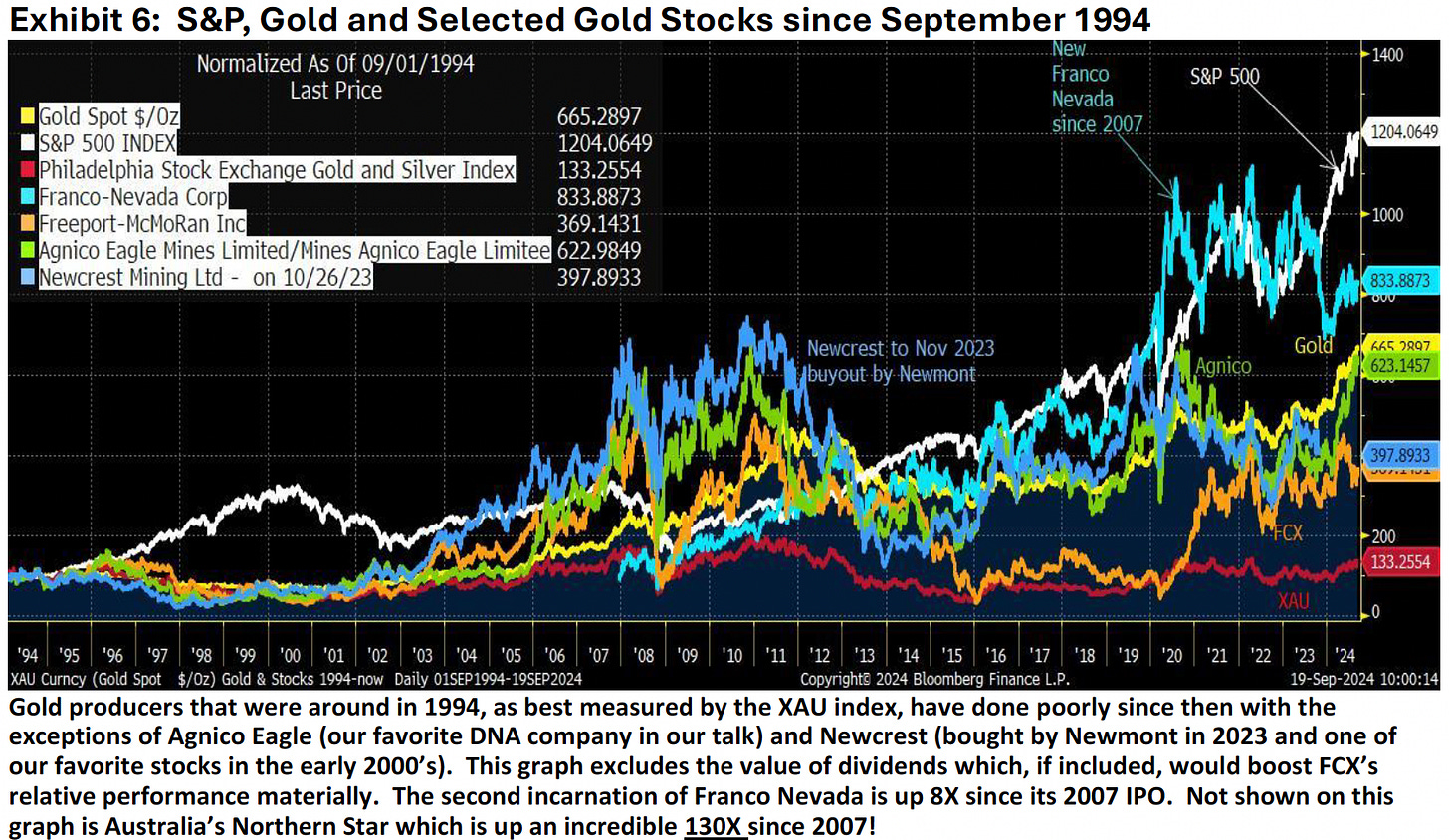

Exhibit 6 shows gold and gold stock performances since 1994. Except for Agnico Eagle, major gold producers as indicated by the XAU have done poorly and have underperformed gold. Franco Nevada since 2007 in its second incarnation has done well but it is a royalty company. Not on the graph is Australia’s Northern Star Resources which has risen from a penny stock in 2004 to A$16 today and created a lot of value for investors.

Gold producers that were around in 1994, as best measured by the XAU index, have done poorly since then with the exceptions of Agnico Eagle (our favorite DNA company in our talk) and Newcrest (bought by Newmont in 2023 and one of our favorite stocks in the early 2000’s). This graph excludes the value of dividends which, if included, would boost FCX’s relative performance materially. The second incarnation of Franco Nevada is up 8X since its 2007 IPO. Not shown on this graph is Australia’s Northern Star which is up an incredible 130X since 2007!

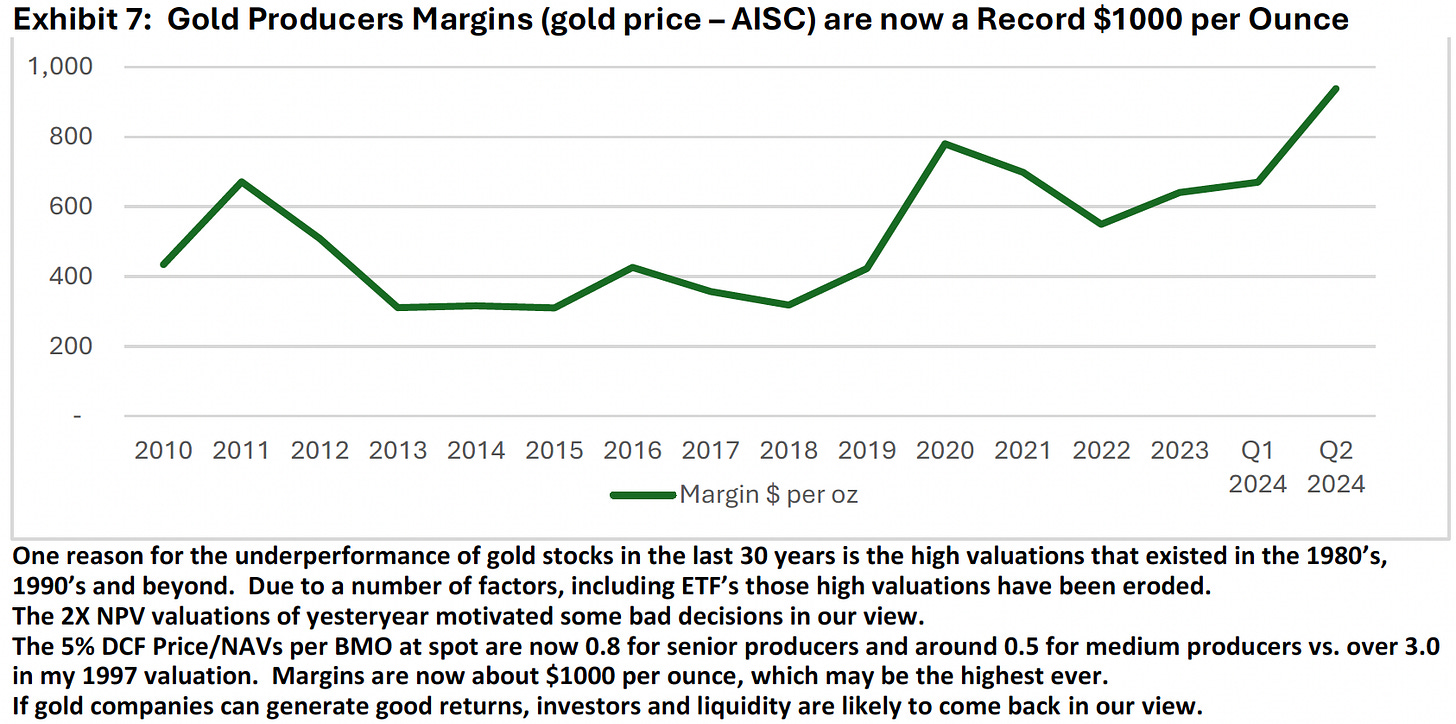

Exhibit 7 looks at current valuations. They have dropped and become competitive with other businesses. These are historic times for gold miners if these prices and margins can be sustained.

Three Impressions from Watching the Industry for 30 Years

The Fall in Gold Stock Multiples Has Positive Implications for Industry Behavior

When gold companies were valued at 2X NPV and/or market capitalization per ounce it was difficult for companies to abandon plans to develop difficult projects. Barrick’s Pascau-Lama project, which always had low returns in our spreadsheets, is one case in point in our opinion. Las Cristinas for Placer Dome in the late 1990’s was another such project. The market’s willingness to fund and pay for such low return projects was part of the problem. Now with multiples roughly half of what they have been and capital less abundant, companies are forced to be better disciplined in allocating capital and seeing maximum operating returns.

Aussie Miners and Contractors Have Been Leaders

I travelled to Australia shortly after that 1994 Denver Gold Show and visited several mines in Queensland, the Northern Territory and Western Australia. The only underground gold mine in Western Australia that I could identify was the Mt. Charlotte mine, still running, that was part of the Kalgoorlie Super pit operations. I flew over countless open pit operations that would soon transition to underground. On those flights I was thinking that Australian miners could learn a lot from the Canadian shaft building underground miners that I knew in the Abitibi greenstone belt in Quebec and Ontario. Boy, was I wrong. Some Canadian Miners including Agnico Eagle have done some great things underground since then. However, during the next few years after 1994 many of those Australian operations would proceed underground efficiently to in excess of 1000 meters using declines only. With relatively large haulage systems that had some historical roots in Tasmania, it seemed like some Aussie underground operations succeeded in mining half of an underground ore body before a Canadian operation had sunk a shaft and mined its first stope. The speed of execution impressed me. I also watched the development of Ridgeway by Newcrest, which was the first sub level cave underground mine in the gold industry. Today, it seems Australian led contractors are leading globally in gold mining including on the process front. Lycopodium for example, appears to be the contractor of choice in Africa. Australian miners have also been better allocators of capital in our view partly because capital markets there have been less generous.

Chinese Processing Abilities Have Impressed

I have only been to one Chinese mine, and I did not go underground. I was not impressed. That was a decade ago. However, I have since visited Chinese nickel processing facilities and watching what they have done in nickel processing has blown my mind. First, in nickel pig iron around 2007 and now producing battery grade nickel and cobalt product by HPAL, Chinese companies have made western companies that have tried for decades to do similar things look inept. The huge numbers of new Chinese engineers would appear to be having an impact as does their growing international experience. We expect material advancement in Chinese gold mining and processing abilities.

Five Pieces of Advice for New Investors to the Gold Mining Sector

These are just some of the things we would suggest for new investors in the gold mining space.

Look for leaders and management teams that have done it before. An example would be the story of Harry Michael and Equinox Minerals. We met Harry when he was a young project manager building the Geita mine for Ashanti Mining and AngloGold in 2001 in Tanzania. He was an impressive guy. He was like a drill sergeant and had us analysts walking seemingly in single file on the mine site visit. We were wondering how brutal he might have been with contractors. Geita was built successfully on budget (a skinny one) and on schedule during very difficult times. A few years later, Mr. MichaeL joined Equinox Minerals who was trying to develop a large copper mine by itself in Zambia. We had been skeptical. However, when they hired Mr. Michael, we were confident Equinox Minerals was going to succeed. Over several years, Equinox’s stock appreciated more than 10-fold culminating in a buyout by Barrick. Tragically, Harry passed away at a young age a few years later. Find out who the “Harry Michaels” are and follow them closely.

Know an analyst’s bias and his/her history. Coming from Barrick, I had several friends there. Accordingly, it was very difficult for me to be critical. On the opposite front, an analyst who was wrong and beaten up recommending a stock to clients will normally be very reluctant to recommend it again even if he or she is more confident that it could outperform. You can find some of that history (recommendations and target prices) by looking up the ratings history and target prices on Bloomberg. You can also just talk to the analysts. Sometimes multiple analysts get beaten up on a stock because of an event and are cautious all at the same time. Many times they are right to be cautious but sometimes not. Understanding an analyst’s bias can make a big difference in understanding where “the street” is on a stock and in adding confidence to your own conviction.

Be wary of investing in a big mining project in a country with little mining history, a small GDP, and/or a sensitive environment. If a national politician must take a political position on a project or mine to get elected, then there will likely be problems. Rio Tinto’s Oyu Tolgoi copper mine in Mongolia, First Quantum’s copper mine in Panama, and Centerra’s former Kumtor mine in Kyrgyzstan are three cases in point. Barrick’s Pasua-Lama project in Chile and Argentina has not been helped by the sensitivity of that mine crossing the border.

Avoid putting value on new process technologies that have not been run successfully on scale. In my nearly 40 years watching the gold mining industry there have been very few material new technologies that have been successful. Autoclaving, which Barrick helped pioneer in the gold industry, has been a success. Heap leaching was a success starting in the 1980’s. Conversely, bioleaching and thiosulphate leaching which were once touted by Newmont, have gone near nowhere. We expect there will be successes in the future, but we will only know when it is tried in the field in scale whether it works.

Finally raise your sustaining capital cost estimates in your model for outlying years. Mining companies tend to do a lot of work and plan well in “next” year’s budget and maybe the year after that. However, beyond year two it has been rare in our experience to adjust capex anything but up.

Closing Remarks

In closing, I would like to thank all my colleagues I have worked with in the industry these past few decades. I would also like to remember my many friends in the industry, including at Barrick who passed away, some way too young, in the years since 1994.

All references to the gold price are per troy ounce.

Rossport Investments LLC specializes in the metals and mining sector. If you would like more information on our work and views, please contact Daniel McConvey at (908) 578-0840 or by email at daniel.mcconvey@rossport.com.

Note: Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results. Forward-looking statements reflect Rossport Investments’ views as of such date with respect to possible future events. Actual results could differ materially from those in the forward-looking statements as a result of factors beyond our control. Investors are cautioned not to place undue reliance on such statements. No party has an obligation to update any of the forward- looking statements in this article.